Today’s challenge is a very easy challenge from Hack the Box. You can find it here. There is no machine to start up, you just download the required files for the challenge. You’ll get a .zip file and the password they provide you is hackthebox.

Today’s challenge is a very easy challenge from Hack the Box. You can find it here. There is no machine to start up, you just download the required files for the challenge. You’ll get a .zip file and the password they provide you is hackthebox.

(kali@vici)-[~/htb/spookypass] $ unzip SpookyPass.zip Archive: SpookyPass.zip creating: rev_spookypass/ [SpookyPass.zip] rev_spookypass/pass password: inflating: rev_spookypass/pass

After unzipping it, we see that it unzipped a directory called rev_spookypass and that directory has a single file in it called pass. When we run the file command on pass, we see that is an executable and that it is not stripped.

(kali@vici)-[~/htb/spookypass]

$ ls

rev_spookypass SpookyPass.zip

(kali@vici)-[~/htb/spookypass]

$ cd rev_spookypass && ls

pass

(kali@vici)-[~/htb/spookypass/rev_spookypass]

$ file pass

pass: ELF 64-bit LSB pie executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, BuildID[sha1]=3008217772cc2426c643d69b80a96c715490dd91, for GNU/Linux 4.4.0, not stripped

Since this is Hack the Box, we can be a little less cautious. However, if you find an executable in the wild, don’t just run it. The better play is to get it into a sandbox and run it there so that it can’t do any damage to your machine or VM on the chance that it is malicious. Warnings aside, here we go..

(kali@vici)-[~/htb/spookypass/rev_spookypass] $ ./pass Welcome to the SPOOKIEST party of the year. Before we let you in, you'll need to give us the password: hackthebox You're not a real ghost; clear off!

Okay. So, we need a password. The file command said that this binary executable is not stripped. What does that even mean? That means that the binary still contains its symbol table and possibly debugging information. The result is that:

- Function names, variable names, and other symbols are still embedded inside.

- It’s larger in size than a stripped binary.

- It’s easier to debug or reverse engineer (e.g., using gdb, objdump, or strings).

Okay, so now we are talking about some good stuff. Since this wants a password and it is checking, it is possible that the password is inside, unobfuscated, and accessible through some simple methods. I’m going to try strings first. What is strings? This description is from the man pages for strings.

DESCRIPTION For each file given, GNU strings prints the printable character sequences that are at least 4 characters long (or the number given with the options below) and are followed by an unprintable character. Depending upon how the strings program was configured it will default to either displaying all the printable sequences that it can find in each file, or only those sequences that are in loadable, initialized data sections. If the file type is unrecognizable, or if strings is reading from stdin then it will always display all of the printable sequences that it can find. For backwards compatibility any file that occurs after a command-line option of just - will also be scanned in full, regardless of the presence of any -d option. strings is mainly useful for determining the contents of non-text files.

What does that get us?

(kali@vici)-[~/htb/spookypass/rev_spookypass] $ strings pass /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 fgets stdin puts __stack_chk_fail __libc_start_main __cxa_finalize strchr printf strcmp libc.so.6 GLIBC_2.4 GLIBC_2.2.5 GLIBC_2.34 _ITM_deregisterTMCloneTable __gmon_start__ _ITM_registerTMCloneTable PTE1 u3UH Welcome to the [1;3mSPOOKIEST [0m party of the year. Before we let you in, you'll need to give us the password: s3cr3t_p455_f0r_gh05t5_4nd_gh0ul5 Welcome inside! You're not a real ghost; clear off! ;*3$" GCC: (GNU) 14.2.1 20240805 GCC: (GNU) 14.2.1 20240910 main.c _DYNAMIC __GNU_EH_FRAME_HDR _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_ __libc_start_main@GLIBC_2.34 _ITM_deregisterTMCloneTable puts@GLIBC_2.2.5 stdin@GLIBC_2.2.5 _edata _fini __stack_chk_fail@GLIBC_2.4 strchr@GLIBC_2.2.5 printf@GLIBC_2.2.5 parts fgets@GLIBC_2.2.5 __data_start strcmp@GLIBC_2.2.5 __gmon_start__ __dso_handle _IO_stdin_used _end __bss_start main __TMC_END__ _ITM_registerTMCloneTable __cxa_finalize@GLIBC_2.2.5 _init .symtab .strtab .shstrtab .interp .note.gnu.property .note.gnu.build-id .note.ABI-tag .gnu.hash .dynsym .dynstr .gnu.version .gnu.version_r .rela.dyn .rela.plt .init .text .fini .rodata .eh_frame_hdr .eh_frame .init_array .fini_array .dynamic .got .got.plt .data .bss .comment

Anything look good in there? Absolutely! Between the string requesting the password and the string welcoming you in is this gem, “s3cr3t_p455_f0r_gh05t5_4nd_gh0ul5”. Let’s see if it works.

(kali@vici)-[~/htb/spookypass/rev_spookypass]

$ ./pass

Welcome to the SPOOKIEST party of the year.

Before we let you in, you'll need to give us the password: s3cr3t_p455_f0r_gh05t5_4nd_gh0ul5

Welcome inside!

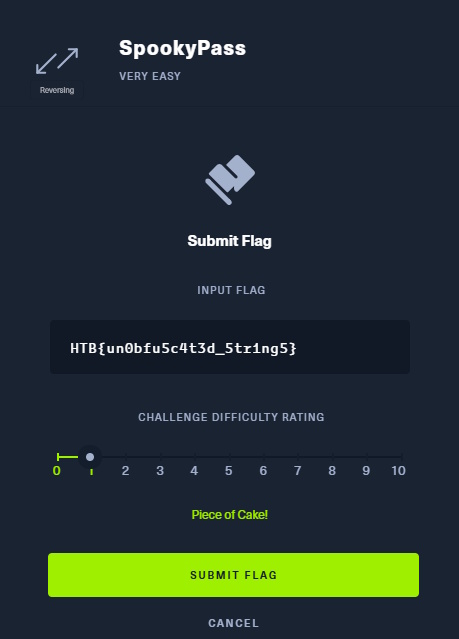

HTB{un0bfu5c4t3d_5tr1ng5}

And there we go. If we put that flag in over at Hack the Box, we win.

There we go! Very Easy, as promised. However, we did get some exposure to learning about unknown files and some very basic skills in prodding those files to see what might be hidden within them. Any questions, let me know in the comments!

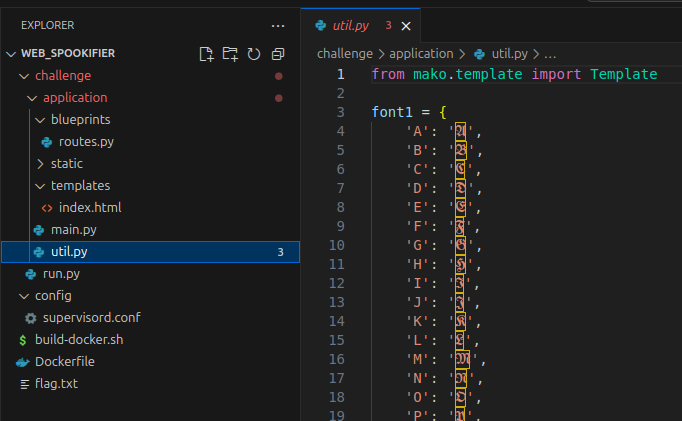

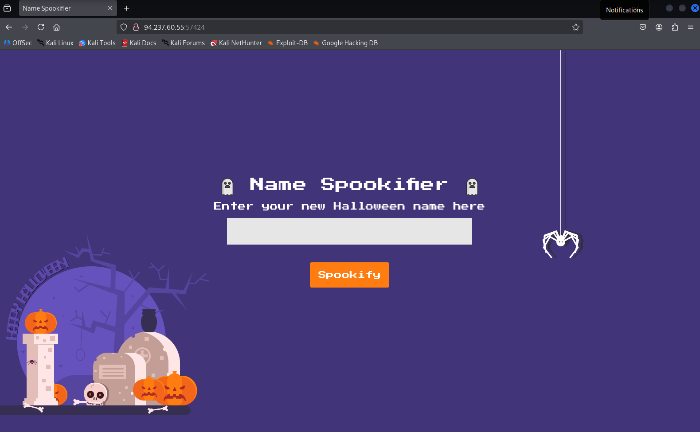

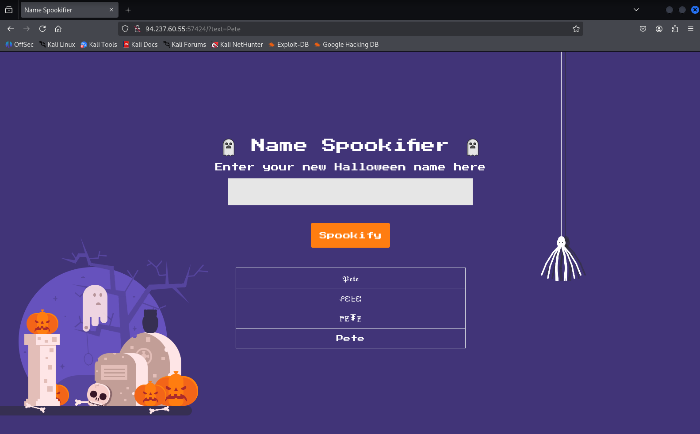

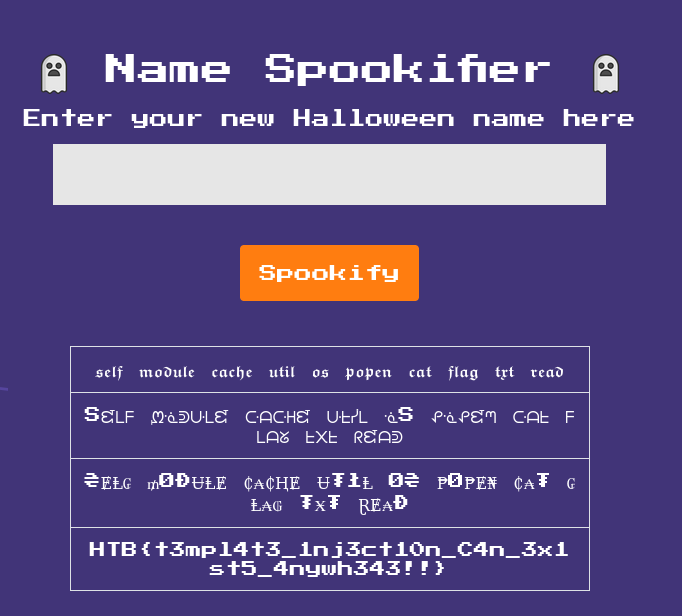

Today, we’re going to take on a Hack the Box challenge called Spookifier. This is a free, retired challenge that you can find

Today, we’re going to take on a Hack the Box challenge called Spookifier. This is a free, retired challenge that you can find

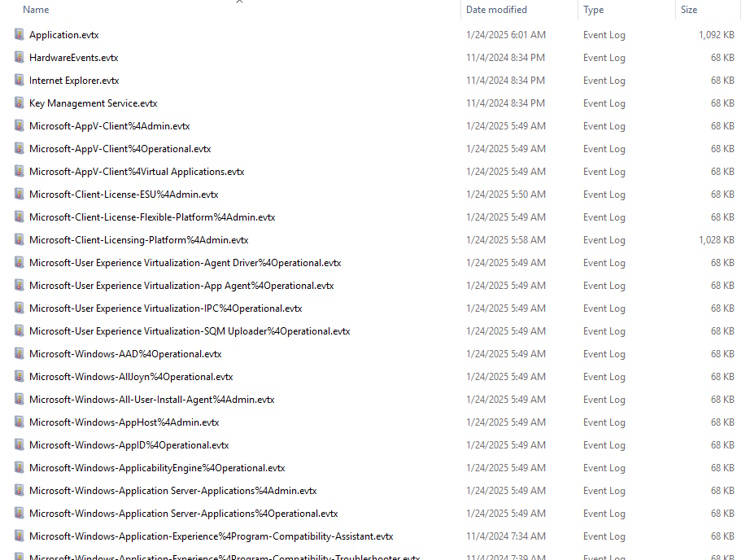

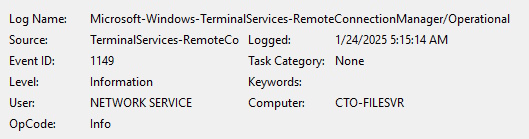

Today, we’re going to go through the HackTheBox Sherlock (Blue Team) room called SmartyPants. It is a retired Sherlock and you can follow along for free

Today, we’re going to go through the HackTheBox Sherlock (Blue Team) room called SmartyPants. It is a retired Sherlock and you can follow along for free

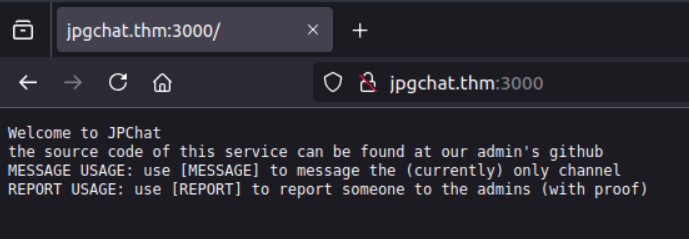

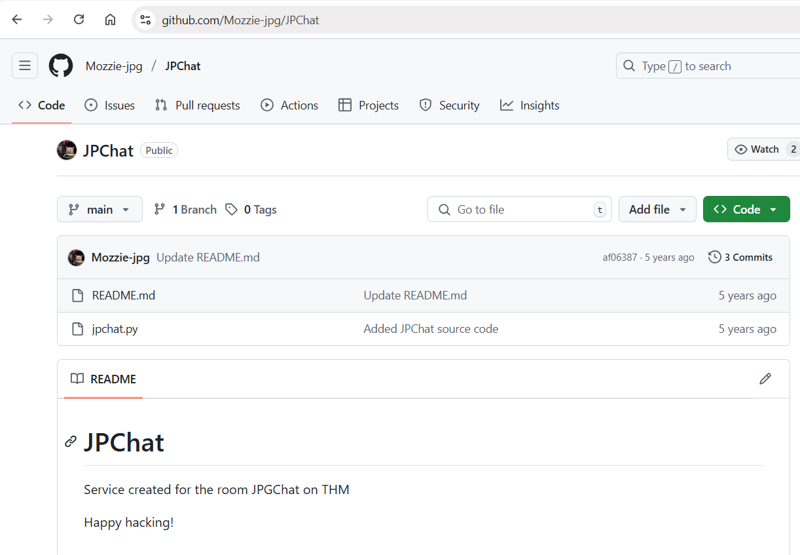

Today, we’re going to do a challenge room from TryHackMe called JPGChat. You can find it

Today, we’re going to do a challenge room from TryHackMe called JPGChat. You can find it

We’re going to keep the pattern going and attack another free Sherlock from HackTheBox called

We’re going to keep the pattern going and attack another free Sherlock from HackTheBox called