Note: Post has been updated below

Salted hashes? Have I decided to blog about breakfast?

Salted hashes? Have I decided to blog about breakfast?

No. By “Hash”, I mean “cryptographic hashes” and by “Salt”, I mean “additional input added to a one way hashing function”. Back in Episode 4 of my Podcast, I talked about a system that was written from the ground up to manage users, passwords, and permissions. During my little rant, I talk about storing passwords as the result of a one-way hashed value, but I didn’t really elaborate.

I realize that many of my regular readers may know this information, but I’ve been surprised at how many that I’ve found who do not. Hopefully, I can shed some light to those who don’t know and also become a viable source in search engine results for when the question is asked.

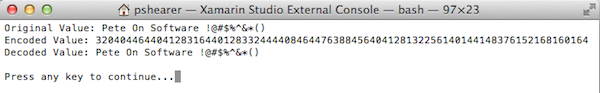

Let’s get the easy part out of the way first. We KNOW not to store plain text passwords, right? Some people know that and choose instead to store the passwords via two-way cryptography, meaning they can encrypt and then decrypt the password to compare it or email it you. That is also a terrible idea. Now, your entire system is only as secure as the security around your decryption key or decryption certificate. You’ve just made an attacker’s job very easy.

The better way to store passwords is to only store the result of a one-way hash. Then, when someone presents their password for authentication, you just hash the input and compare that to what you have stored in the database. However, even though this is good, it is still not right.

Take this for instance. Here is a sample table with hashed passwords.

| user | password |

|---|---|

| pete | b68fe43f0d1a0d7aef123722670be50268e15365401c442f8806ef83b612976b |

| bill | 59dea5f67aea4662c26a5ac6452233e783407d55c4f96d6c4df6f0d7c06c58af |

| jeff | b68fe43f0d1a0d7aef123722670be50268e15365401c442f8806ef83b612976b |

| andy | b6642c42bd670b0c070dd45d087877a4bc8d6ee29c88df59273ea48ed72b76c4 |

| ron | b68fe43f0d1a0d7aef123722670be50268e15365401c442f8806ef83b612976b |

Right away, you should be able to see a problem. The hashes for pete, jeff, and ron are all the same. A common attack against hashed passwords is a rainbow table. In that case, dictionary words (or common known phrases) are pre-hashed and those hashes can then be compared against a compromised database. Let’s take a look.

| password | SHA-3 (256) Value |

|---|---|

| password | b68fe43f0d1a0d7aef123722670be50268e15365401c442f8806ef83b612976b |

| letmein | ceaa5fd0a764ad8202f43f2efc860d8c7472911ca9d1ccea2dc232713ae1fc0d |

| blink182 | aadfce5bdba224673c168fb861f45cdd6ebf4e34d35001ae933bd53b7f6b337f |

| password1 | abbe6325ea0d23629e7199100ba1e9ba2278c0a33a9c4bfc6cd091e5a2608f1a |

Now, by comparing, we can see that the password for pete is the word password. That means that the password for jeff and ron are also “password”. By only cracking one hash, we gain access to two other accounts. This is not good.

The fix is to “salt” the password before hashing it. You want that salt to be a unique value. Some people create a random value and then store the salt alongside the password in another database column. Others derive the salt from something like the row’s primary key, etc. Either way is fine (as long as your derived value won’t change).

Now, let’s examine our user table.

| user | salt | password |

|---|---|---|

| pete | I7Yrs9THQyLxpVllSwbf | 9b7ec6d82075a9e7d8227897e8919785031b9a7cdab5750dea044390d1fd1f46 |

| bill | K0kJJCQcVVqfLzykcpbP | 297d00ae29ff3c32fe874c00d0154085ac862a154b061c17cd465de7f1cdee9a |

| jeff | NwV7PdmPUKY6GgScEUqu | c2936d36583d0513980e496005872e4954d142ed823b7b0b1abf28211efc538f |

| andy | GpHrXjbQRTjObZWM7jbd | 0338bd60f7d761ce9c8922087e87c9ccb7936bb5f9c5c28d72fd28f4d8708e6b |

| ron | iHh8SX7fQEF2WFUOfxEp | 07f459276c9be7d63aa8d57dac7468c8b16dd4367e91615fb9972543a707c403 |

We notice right away that none of the user’s hashes are the same. I didn’t change the passwords, but the salt values made the passwords unique so that they all hashed differently. We can no longer tell whose passwords are identical. Also, our plain dictionary attack no longer works. Even though we’ve telegraphed to the attacker what salt to use, the attacker would have to generate rainbow tables across their entire dictionary for each individual salt.

This isn’t 100% secure (nothing is), but this is a best practice and certainly will slow the attackers down. This method of storage, combined with strong passwords should keep your data as safe as it can be.

Thoughts? Disagreements? Share them in the comments section below.

EDIT (5/16/2014): I talked on my podcast referenced above about how easy it is to get behind or to overlook things if you do your own security as yet another reason NOT to do it. I recommended just using existing products or frameworks that have already been hardened over rolling your own. As a perfect example, I talked about doing all of this, but forgot about bcrypt (and others) that are much more secure, salt the value for you, and already have libraries in all of the major languages.